By The Runner Staff

When students arrived on campus on Oct. 28, many received news of a tragic development regarding one of our peers. That day, word had spread that Los Ortiz, a California State University, Bakersfield student and Kappa Sigma fraternity member, had died by suicide.

While students and friends of Ortiz will inevitably question how this came to pass, we should also ask: How can we prevent another incident? Our answer is two-pronged. First, for those struggling with depression, anxiety, or stress, don’t be afraid to ask for help. Second, if you notice someone struggling with these issues, actively encourage them to seek therapy. We live in a world in which we encounter pressure-filled situations at all times.

As students, each class, test and assignment generates stress-inducing factors, including concern for our grades, our comprehension of course material and our ability to designate time for assignment completion and studying. As people, we must also manage our friendships and familial relationships, physical and mental health and the potential need for employment among myriad other needs, all of which produce stress and emotions that can complicate our stress management. Of course, these obligations do not exist within a vacuum.

As many can attest, what happens within one area of our lives can greatly affect us in others, and what first appeared to be our manageable list of existential obligations becomes increasingly muddled amidst the unexpected emergencies and consequences of life. For the 30 percent of college students that, according to the 2013 National College Health Assessment, suffer from depression so severe they have difficulty functioning each day, these various stresses feel impossibly heavy. Each day becomes a challenge, and with each unresolved task, the next day becomes even more burdensome.

As friends of those who may be suffering from depression, this is where we become involved. If we are to help combat both the signs and development of depression in others, we must take it upon ourselves to be an active agent in alleviating others’ sorrow.

If people experience a hardship of any kind, we must be willing to empathize with them and listen to him or her. We must be willing to function as a person in whom people can confide, allowing others to slowly relieve themselves of their emotional burdens. If we notice someone is socially withdrawing – or even refraining from their favorite activities – we must be willing to persistently ask about another’s thought processes, what emotions they’ve been experiencing and how they are managing any problematic thoughts or feelings. We similarly must understand that we live in a society in which mental illnesses and their victims face significant stigmas that discourage the pursuit of treatment.

Unlike physical ailments, which people universally accept as requiring the advice of medical professionals, mental illnesses are seen as evidence of a deficiency within their victims. Nobody will legitimately blame someone who suffers from pancreatic cancer; surely it wasn’t the person’s fault that such an illness developed. But when mental illnesses are concerned, our society at-large blames the victims, calling them crazy or unstable.

The stigma associated with mental illness ultimately serves no one. Knowing this, if we recognize that a person needs professional treatment, we must both advocate for pursuing help and encourage the person in need, reminding him or her that depression is not a shameful secret but an illness that necessitates treatment. This also means that we must be willing to physically walk our friends to the university counseling center and schedule an appointment for them if circumstances dictate such an action. And if you’re someone in need of help, pursue treatment.

Schedule an appointment with a counselor, or accept an appointment if one is made on your behalf. Allow people access into your thoughts and feelings, and rid yourself of the belief that you are a burden to anyone.

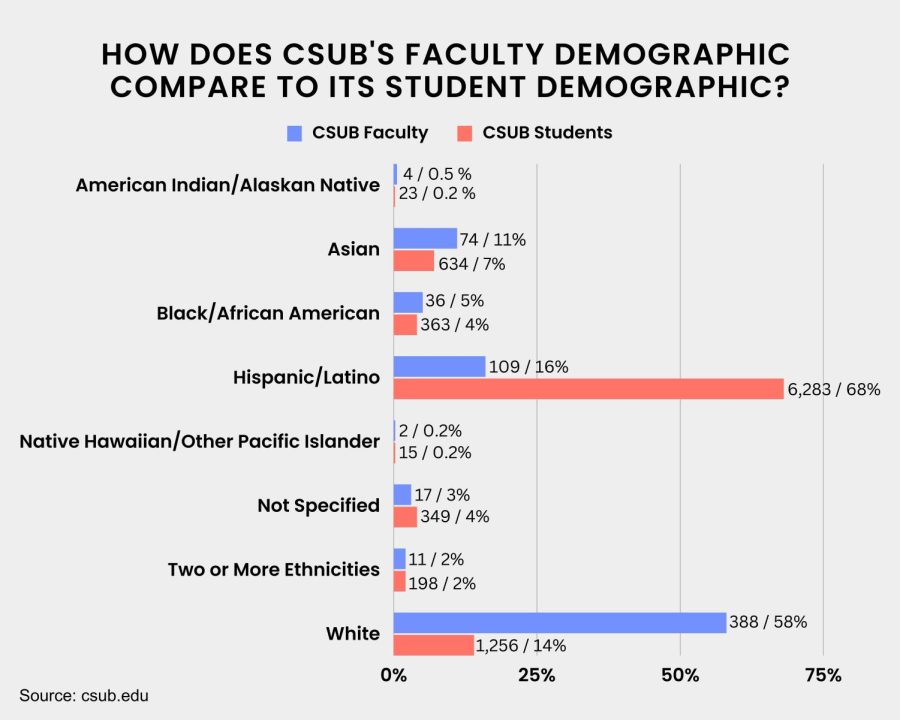

Per Dr. Michael Harville, a counselor at CSUB, suicide is the second-leading cause of death among college students, and roughly 10 percent of students will have suicidal thoughts. With 8,716 students attending CSUB, that means 872 will face suicidal thoughts.

That is 872 students too many. None of this is to say that Ortiz’s passing was the result of depression. We will perhaps never know the exact reason for his suicide – but if the university and its students can learn anything from this tragedy, it is ultimately that suicide and depression can be prevented, with us being the catalysts for improvement.