Features Editor

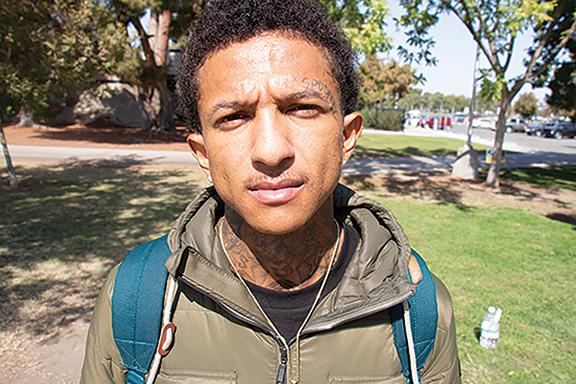

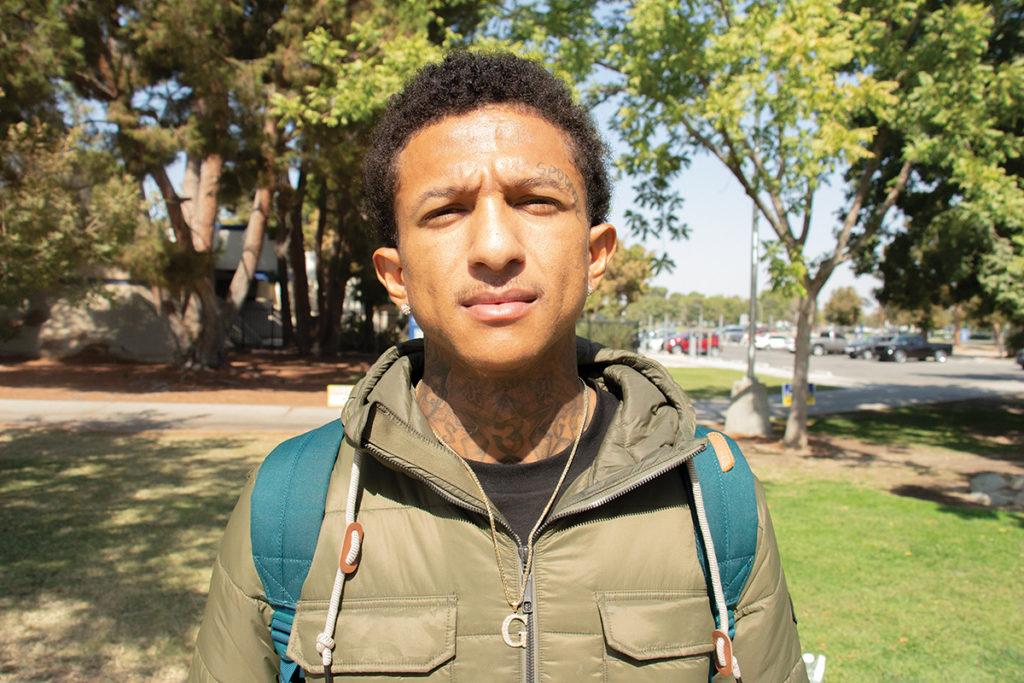

Undeclared sophomore Darrius Noel is all too aware that when people look at him, the first thing they see are his face tattoos.

“I feel like once [people] get to know me and I speak, they’re like ‘oh, he’s cool,’” Noel said about people who judge him based on his appearance. “As far as professors, they all love me.”

Twenty-five year-old Noel has—at the time this was written—three tattoos on his face. The number three below his temple, the word “SPOONIE” written above his left eyebrow, and a memorial tattoo above his jawline dedicated to his son who passed away at the age of three.

During a five-year and nine-month stint in prison for strong-armed robbery with a gang enhancement, Noel received all of his facial tattoos, in addition to others.

“Prisoners are smart,” Noel said of an inmate’s ability to take the motor from a CD player, a guitar string for a needle, a Bic pen for its barrel, and ink made from baby oil to assemble a tattoo machine.

The hazards of getting a tattoo in prison, as well as out of someone’s house, include not being able to prepare for it with proper sterilization as well as not being able to care for it once it’s there.

Jayson “2Cents” Macross has been a professional tattoo artist since 1996.

“It’s not the correct procedure to make sure that you have a sterile environment, and it’s going to set you up for a lot more possibility of infection, including communicable diseases like Hepatitis and Staph,” 2Cents said.

Noel said that at the time he got his face tattoos, he was in a dark moment of his life.

After being placed in the Segregated Housing Unit for 15 months, Noel began to question if he wanted to be a stereotype of the black man.

Reading self-help books occupied his time while in the SHU.

“That’s when I had time to sit down and reflect on a lot of things,” he said.

Noel realized that as a young man he was lost and didn’t value or love himself. He had originally believed that he had to be a product of his environment.

“I used to say I would go to prison when I was younger,” said Noel. “Because it’s glorified as something you had to do to earn your stripes.”

Noel said he considered it his challenge to maintain his new mindset after being returned to the general population, with its drugs and violence. That would be his test before he could go home.

Noel admitted his mother was upset upon seeing him with face tattoos after he was released, but she accepted him for who he is.

A year after being released from prison, Noel ran into someone who told him about CSU Bakersfield’s Project Rebound. A program developed for the formerly incarcerated.

Michael Dotson is the Project Rebound Coordinator for CSUB’s campus.

“We have approximately thirty-two [formerly incarcerated students] enrolled,” Dotson said.

The program works with those who have been or currently are incarcerated by preparing them for college through mentorship. Tutoring is also provided for students before and after enrollment.

“Growing up the way some grow up, they never know that college is an option,” Dotson said.

Noel jumped on the opportunity as it presented itself.

“In prison I used to always see myself going to college,” Noel said.

Since attending CSUB, he said that he has struggled with staying in college but wants to finish what he started.

“A quitter never wins and a winner never quits,” said Noel.

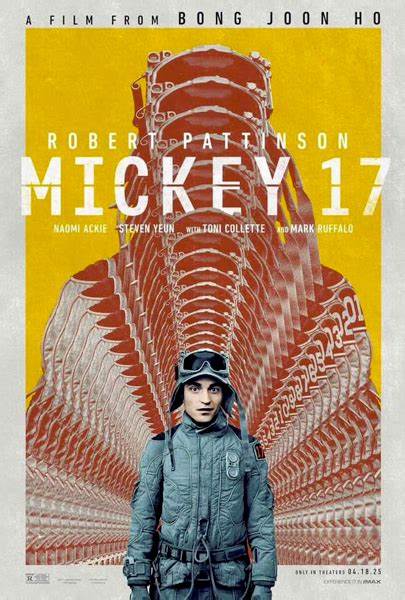

While musicians like Lil Wayne and Post Malone have made face tattoos trendy, Interim Chair of the Sociology Department, Dr. Rhonda Dugan said for the average person, face tattoos may work against them.

People who have tattoos on their face are more likely to be identified if they commit a crime.

In Western culture there is the stigma that having a face tattoo is indicative of poor-decision making— while in a culture like the Polynesian, having one’s face tattooed is tied into their history.

Dugan said that this stigma is unfair.

“Just cause it’s there doesn’t make you bad,” Dugan said.

Society has grown to embrace tattoos, as they carry meaning for each individual, however it may take an unknown amount of time before facial tattoos are viewed as workplace appropriate. Noel has never had to experience the reality of applying for a job with face tattoos.

“Thankfully, I never had to like really go get a job, I’ve always made it work,” he said.

In the event that Noel should want to remove any of his tattoos, laser tattoo removal would be an option.

Deanna Hellmund is the Aesthetic Medicine Manager at Beautologie Cosmetic Surgery and Medical Aesthetics’ southwest Bakersfield location.

“What’s nice nowadays is that there is something that you can do, you know back in the day it was like you got a tattoo, that was it,” Hellmund said.

The process takes multiple sessions, which range in price from $200 to $675 per session based on size. Prison tattoos, done with improvised ink, are easier to remove than tattoos made with professional ink.

Beautologie also offers people who have unwanted and gang related tattoos the opportunity to have them removed for free. If someone wants to remove a tattoo, they have to write into the clinic and tell the story behind the tattoo and why they want it gone. The waitlist for that is estimated to be three years.

However, Noel expressed no regret about any of his tattoos, and planned on getting another one—a portrait of his late son on the side of his head.

“I wouldn’t change it, I wouldn’t take nothing off. Everything I did for a reason,” Noel said. “They’re a part of me.”

Noel said that he wants to become a motivational speaker for children who are where he once was.

“We can’t help what we’re born into,” Noel said. “But we can predict what we should have in this life.”